In November 1971, Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan entered the Record Plant recording studio in New York City to record adaptations of Ginsberg’s own poetry, arrangements of poems by William Blake, and a few Ginsberg-Dylan original songs. The resulting recordings are rough and ragged. However, the most successful work is “Vomit Express,” which constitutes a shotgun wedding between topnotch Ginsberg-ian exuberance and The Basement Tapes:

Ginsberg wrote about some of his recordings collected on the Hal Willner-produced box set titled Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems And Songs 1949-1993, and it includes the following reminiscence about how the 1971 collaboration with Dylan began:

“Dylan had come to hear a poetry reading at NYU’s Loeb Auditorium, standing in the back of the crowded hall with David Amram. We were on stage with a gang of musician friends, and Peter [Orlovsky] improvised, singing, ‘You shouldn’t write poetry down but carol it in the air, because to use paper you have to cut down trees.’ I picked up on that, and we spent a half an hour making up tuneful words on the spot. I didn’t know 12-bar blues, it was just a free-form rhyming extravaganza. We packed up, said goodbye to the musicians, thanked them and gave them a little money, went home, and then the phone rang. It was Dylan asking, ‘Do you always improvise like that?’ And I said, ‘Not always, but I can. I used to do that with [Jack] Kerouac under the Brooklyn Bridge all the time.’”

Ginsberg’s improvisation abilities must have sparked something for Dylan. Only a few months earlier in March 1971, Dylan was in the studio and the drummer Jim Keltner recalled that he was composing lyrics in the moment:

“I remember Bob … had a pencil and a notepad, and he was writing a lot. He was writing these songs on the spot in the studio, or finishing them up at least.”

Going back a few years before, Dylan had engaged in improvisational songwriting with members of what became The Band as part of The Basement Tapes. Ginsberg himself was name-checked during one delightfully goofy, stoned day, forever memorialized as “See You Later, Allen Ginsberg,” a recording that apparently later became a favorite in Ginsberg’s office. The extemporaneous nature of The Basement Tapes period was fresh in Dylan’s mind because only a few weeks before attending Ginsberg’s NYU performance, he had recorded three Basement Tapes songs with Happy Traum to be included on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. II.

Continuing with Ginsberg’s account of the 1971 collaboration with Dylan:

“[Dylan] came to our apartment with Amram and a guitar, we began inventing something about ‘Vomit Express,’ jamming for quite awhile, but didn’t finish it. He said, ‘Oh, we ought to get together in a studio and do it’ [and] then showed me the three-chord blues pattern on my pump organ.”

With studio time at the Record Plant booked, Dylan began rounding up players to accompany Ginsberg. Amram would need to be involved since he had also attended the NYU performance. Dylan must have thought that Traum would continue to help summon the ad-lib-friendly, Basement Tapes feel as he was also enlisted, according to this Traum recollection:

“Bob Dylan called me one day and said: ‘You know, you should learn how to play the bass.’ I didn’t know why he was saying that, but I figured, okay, I’ll learn how to play the bass. So I borrowed a bass and an amp and practiced for a while. Maybe a month later he called me again and said ‘Bring your bass to the city, because I’m doing a session with Allen Ginsberg and I want you to play on it.’ That was kind of strange, New York City is full of great bass players, I don’t know why he wanted me. Anyway, I went into the city and I brought the bass with me. I had never met Allen Ginsberg before. It was Allen, Peter Orlovsky, his partner, David Amram, John Sholle, Bob Dylan who was organizing the whole session…It was a crazy session. We were putting music to Allen’s poetry. Allen was singing and playing his harmonium, which he pumped with one hand and played with the other. It was a long, all-day session. It was crazy, there were beat poets there, Gregory Corso showed up and was causing all kinds of havoc because he wanted all the attention for himself. There was a Tibetan Buddhist lama woman who was blessing everybody. It was just a really wacky scene (laughs).”

Traum’s memory is certainly backed up by the recording. Dylan plays a quick guitar introduction and the chaos of the assembled group begins immediately. Amram’s piano part sounds like it could be the beginning of a tango, but, in fact, he plays the same chords as Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” There’s a penny whistle or a recorder in the mix. Though Ginsberg is clanging along on his finger cymbals, it’s Dylan who provides the primary rhythm for the song with his acoustic guitar. Ginsberg handles the lead vocals, but the entire “wacky scene” joins in for the chorus, whooping it up as they sing:

I’m going down to Puerto Rico

I’m going down on the midnight plane

I’m going down on the Vomit Express

I’m going down with my suitcase pain.

Ginsberg provided a bit of background on the song’s title and premise:

“‘Vomit Express’ was a phrase I got from my friend Lucien Carr, who talked about going to Puerto Rico, went often, and we were planning to take an overnight plane a couple of weeks later, my first trip there. He spoke of it as the ‘vomit express,’ poor people flying at night for cheap fares, not used to airplanes, throwing up airsick.”

This insight by Ginsberg demonstrates that everything in the song is not, in fact, a recounting of a trip to Puerto Rico, but rather Ginsberg anticipating what will happen on a journey he hoped to take with Carr. So, “Vomit Express” is a tale of expectation and an extended fantasy. Ginsberg tries to set some guardrails for himself before the trip: “Me and my friend, no we won’t even drink. / And I won’t eat meat, I won’t fuck around.” With these restrictions in place, Ginsberg prepares for an epiphany of some sort:

Go out, walk up on the mountain, see the green rain

Imagine that forest, finds, get lost,

Sit cross-legged and meditate on old love pain,

Watch every old love turn to gold.

It’s a beautiful perception by Ginsberg to take “old love pain” and transform it through an aspirational act of alchemy: “every old love turn[s] to gold.” This bit of beatific insight is then released from his body, saying that he will “vomit my holy load.” With this washing away of pain, Ginsberg decides to abandon the limits that he has set for himself. He will leave the mountains and the “green rain,” return back to the city and “walk the streets in shock.” Ginsberg then fantasizes about a sexual encounter using particularly raw language. This fusing of pain, euphoria, the visionary with the profane is a quintessential Ginsberg-ian romantic touch. With that, the duo return to their normal lives, “Back to earth, to New York garbage streets and fly.” To complete the journey and process everything, Ginsberg imagines himself turning off the air conditioning in his apartment so that he can “sit down with my straight spine and pray.”

Ginsberg’s singing throughout “Vomit Express” is certainly irregular but not without charm. Sometimes his delivery is similar to Lou Reed, while other times it’s hard for him not to be influenced by Dylan, especially when Ginsberg lifts his voice to a higher register as during the “rise up out of this mad-house nation” line. In other instances, it’s clear that Ginsberg hasn’t figured out how to deliver a certain line or adjusted the lyric to make it fit the meter. This can be felt acutely when Ginsberg hurriedly sings: “Seen from the heart, maybe the four buddhist normal truths / Existence is suffering, it ends when you’re dead.” Still, the words and imagery are beautiful and the assembled group answers by singing the endearing chorus, so everything feels resolved. At one point, Ginsberg messes up the timing and the background singers don’t join him for the chorus. The solution? A penny whistle solo, of course! Soon, “Vomit Express” fizzles out and winds to a close.

Dylan and Ginsberg would go on to record a number of songs during the week-long session, including “Going To San Diego,” “Jimmy Berman Rag,” and “September On Jessore Road.” The intention was for all these tracks to be released by The Beatles’ Apple Records, but those plans fell through. Ginsberg would later record music with famed producer John Hammond as well as with music collector, experimental filmmaker, sometime flat-mate, and pocket change beneficiary Harry Smith that would be released on a 1983 compilation called First Blues.

Out of all of these recordings, “Vomit Express” stands out. It demonstrates the Basement Tapes feel of “See You Later, Allen Ginsberg” or “Bourbon Street,” thus synthesizing Dylan’s yearning for improvisation as well as Ginsberg unique expression of anticipation and fantasy. “Vomit Express” captures the disarray, pandemonium, and lawlessness inherent to creating spontaneous art, revealing the evident joy in making music that both Dylan and Ginsberg set out to find together.

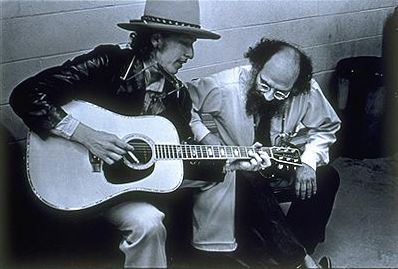

Photo: Elsa Dorfman, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons.

2 thoughts on “Allen Ginsberg & Bob Dylan Ride the “Vomit Express””