In 1987, Paul McCartney invited Elvis Costello to write songs together. Over a series of sessions, they created a body of work from which both artists pulled selections for various albums over the years. The songs written by this partnership were used to augment their own individual work, filling in cracks when either member needed a different voice or perspective while creating the story of a complete album. The McCartney-Costello team produced an album-worth of recordings in the form of demos for each of the songs they jointly composed. The demos were performed by the duo in the instant after writing each song while the flash of inspiration was at its peak. An unofficial album circulated as a bootleg for years before McCartney officially released most of the demos as part of a 2017 expanded, deluxe re-release of his Flowers in the Dirt album. The collection of McCartney-Costello demos constitute one of the great lost albums of the 1980s and count among the best work that either created as a solo artist. The following post breaks from the Recliner Notes template of only focusing on a single song and instead considers the entire body of work because of the fascinating pieces that contribute to the overall mosaic produced by this pair of songwriting masters.

According to a 1988 story in Musician magazine, it was McCartney who initiated the idea that the two should work together according to Richard Ogden, McCartney’s personal manager at the time:

“A fair bit of thought went into Paul’s decision to approach Elvis Costello. Paul felt it was helpful that they had both an Irish heritage and Liverpool family roots in common. But one of the things Paul liked best about Elvis’ songwriting was his strength as a lyricist. Paul sensed his own melodies and ideas could be excitingly compatible with Costello’s literate style.”

Costello provides a bit of context for their working style in his 2015 memoir Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink:

“We worked in a room above Paul’s studio in East Sussex, sitting on two couches across a low table with a pen, a notepad, and a guitar apiece.”

McCartney later recalled the process of the duo writing together and extended praise towards Costello:

“It was like having two craftsmen sitting down. He is into that aspect of songwriting. He knows much more about music history than I do, and it was good.”

Viewing the dynamic between the two, McCartney held a home field advantage since they were writing and recording in his own home studio. But there was also a power imbalance as it tilted towards Paul because, well, he is Paul McCartney from The Beatles. This recognition is especially forceful for Costello since he qualifies as a first generation Beatles fan as proven in an appreciation of The Beatles that he contributed to Rolling Stone in 2004:

“I first heard of The Beatles when I was nine years old…I was exactly the right age to be hit by them full on. My experience — seizing on every picture, saving money for singles and EPs, catching them on a local news show — was repeated over and over again around the world. It was the first time anything like this had happened on this scale.”

Costello had even considered naming one of his earlier albums P.S. I Love You after the early Beatles tune. Costello writes in Unfaithful Music that he needed to rise above his personal history as a fan of McCartney and The Beatles to validate his presence:

“I was almost certain that I shouldn’t turn up in my short trousers with my Beatles Fan Club Card in the top pocket.”

Continuing on this theme, Costello commented:

“I’ve seen people, quite eminent people, completely lose their mind in his company. I didn’t want to turn up and be kind of bothersome in that way. I wanted to get something good done. Something that justified the invitation.”

Over the weeks they worked together, the pair’s approach emerged, as recalled by Costello in Unfaithful Music:

“Both of us seemed to like working fast, firing the ideas back and forth until a song took shape out of just one line of melody, a couple of unusual changes, or some lyrical cue….Whenever Paul and I completed a number, we’d go downstairs to the recording studio on the ground floor and cut a demo with just two guitars or the piano.”

The first of the McCartney-Costello demos to be considered is the song “The Lovers That Never Were”:

A little boogie woogie piano starts the track before setting a minor chord. The song is composed as a directive to a long-sought-after-lover asking if there’s any chance for them as a couple. There are hints from this woman that she may feel the same, but this message is an open declaration and a plea for clarity. Costello and McCartney exhibit beautiful turns of phrase throughout singing “All of the clocks have run down” and repeating it later in the song and adding “Time’s at an end.” There’s a narrative arc to the song as it builds to a conclusion with the imagined “parade of unpainted dreams.” It’s a gem of a song to be sure and confidently realized in a remarkable performance by the duo which includes piano, acoustic guitar, and extraordinary harmonies. In Unfaithful Music, Costello recalls this particular demo writing that “The Lovers That Never Were” was:

“One of the best songs that Paul and I wrote together [and] was written at the piano. It was a sweeping, romantic tune that could almost have been an epic Bacharach ballad.…I’d say the rough recording of ‘The Lovers That Never Were’ is one of the great unreleased performances of Paul McCartney’s solo career…I was playing the piano when Paul opened up behind me in a wild, distorted voice that was almost like the one he used on ‘I’m Down.’ I just kept staring down at my hands at the piano, saying to myself, Don’t mess this up, while trying to remember to chime in on the few lines that we’d agreed I’d sing.”

Despite knowing the expectation from McCartney as well as himself that he is an equal partner, Costello cannot help but be overwhelmed by the situation. Costello certainly meets the moment, especially with his contribution to the harmonies. In listening to this recording and the rest of the demos, the vocal compatibility of McCartney-Costello is at the level of the great duos of pop music, including The Everly Brothers and, well, Lennon-McCartney. The echos with Paul’s more famous singing partner is no accident as noted by Costello:

“I can’t sing above him so I would naturally harmonize below. Which is often the relationship of Lennon and McCartney’s harmonization. That would draw some comparison. Hey, I sing through my nose some of the time. What can I do? I learned how to sing two-part harmonies from singing along with Beatles records. So of course, the minute I put my voice next to his, with the somewhat harder edges in my voice, it naturally created some sort of regional echo. I call it the Mersey cadence. I wasn’t even born in Liverpool. My family’s from Liverpool. But I’ve got a lot of those sounds in my voice.”

The parallels with the famous Beatles harmonies continue with the next song, “Tommy’s Come Home”:

A complex song, “Tommy’s Come Home” shifts perspectives in each verse and then uses the middle-eight sections to comment on the rest of the song. In the first verse, the pair incorporate the feel of the song within the text of the composition: “the rock-a-bye rhythm in the song of the rails.” It’s a song that is easily imagined as an Everly Brothers song, though hearing McCartney and Costello harmonize on the word “home” in the chorus recalls the purity of the Lennon-McCartney vocalization of the same word in “Two of Us.” Costello commented on the process of creating “Tommy’s Come Home” as well as their specific working relationship:

“Paul made the first musical statement. But if you listen to that song, who do you think wrote that? Probably me, less known as a melodist than him. But I think I was the one who suggested [hums the chorus]. Often we exchanged the role as we were doing it because it wasn’t considered. All these theories, they don’t exist because of who I am. They exist because of who he is and all these associations that people want to read into. None of that was any part of writing any of these songs. It was almost fun really. It was really seeing what we could get. . . . The image of the hawk hovering over the little animals in that song. I said, ‘How do we get that in the story?’ And I had the idea of a war widow on a train, and somehow both of those images ended up in that song. That’s proper collaborating. It’s not theoretical. It’s actual practical work.”

The next song — “Twenty Fine Fingers” — show the duo shifting songwriting modes:

It’s a rocker with two acoustic guitars and a drum machine. We hear Costello counting the song off before the pair start singing which demonstrates the endearing immediacy of these live demo recordings. Even for a straight-forward rocker, “Twenty Fine Fingers,” there are subtle and compelling chord progressions and melodic touches. Removing the drum machine sound, the song could sit perfectly well within Please Please Me, My Aim Is True, or even a contemporary country album.

“So Like Candy” is not a song that one would imagine fitting into a contemporary country album:

The song is another clever bit of writing as they play off the woman’s name of Candy by including sticky and sweet descriptors throughout. It has the feeling of a short story or a novella as there are hints of something more sinister at play. The duo write about Candy as she appears in a picture early in the song and then the narrator admits later that it is in fact him with Candy in the photograph. Phrases such as “what did I do” and “oh no, not that again” suggest that the narrator isn’t aware of his own actions. Everything is ambiguous about the conclusion of the affair, nothing is explicit. The song reveals itself as more than simply an ode to a woman but is actually a portrayal of the narrator himself through his telling of Candy.

“So Like Candy” feels more like a Costello song than one by McCartney because of the ominous tone, but also because the song was first released as a solo Costello number. After the duo wrote and recorded the demo, Costello would go on to record the song on the 1990 album Mighty Like A Rose since McCartney decided to not record it himself. Listening to Costello’s solo recording after being exposed to the original demo, it is missing something, namely Paul. The demo demonstrates the pair’s easy-going manner as the guitars are simpatico with each other and the harmonies are unimpeachable. McCartney and Costello should always sing with each other on their joint compositions.

The harmonies are again at a high level within the song “You Want Her Too”:

It’s a beautiful performance of an intricately constructed song. Both McCartney and Costello have reflections on its composition. Paul said the following to Rolling Stone in 1989:

“You can take [‘You Want Her Too’] two ways. It’s either a conscience talking to him or another guy. We imagined a Tom and Jerry cartoon, where there’s an angel and a devil above, and one says, ‘Go ahead, do it,’ and the other says, ‘No don’t do it.'”

Costello wrote about “You Want Her Too” in his memoir:

“The song was supposed to be like one of those old Hollywood movie sequences in which the hero is tempted by a little devil on one shoulder and consoled by an angel on the other. I knew what people would say if Paul sang all the sweet lines and I had the sarcastic replies, but as Paul said later, ‘It was just hard to resist.’”

It’s amusing that they are knowingly playing off their public personas in their interpretation of the text. As one can’t help but do in responding to the McCartney-Costello demos, “You Want Her Too” has echos of Beatles songs as the answering vocals recall the Greek chorus commenting on the action in “She’s Leaving Home” as well as John answering “It can’t get much worse” to Paul singing “It’s getting better all the time” in 1967’s “Getting Better.”

The next song, “That Day Is Done,” led to the biggest conflict in the McCartney-Costello collaboration:

The song is the least Beatles-y out of all of the duo’s demos, though Paul’s vocals confirm that he is effortlessly the best harmony vocal singer in the business. “That Day Is Done” has a gospel feel and prefigures Costello’s future New Orleans-inspired compositions and recordings, especially with the Allen Toussaint-esque piano in the demo.

On the day that they were discussing how to record “That Day is Done,” Costello understandably suggested using a New Orleans brass band as musical accompaniment. Instead, McCartney countered with English synth-pop band The Human League as collaborators instead. That comment forced Costello to leave the studio to calm himself down before he said something untoward at his writing partner. McCartney later recalled their disagreement:

“This is one of the rules of my game. I will say stuff, any idea that comes into my head. And if you don’t like it, you just tell me and I’ll probably agree. But my method is to throw out a lot of stuff and whittle it down. [Pause.] Actually, he was really not a fan of The Human League. I like ‘Don’t You Want Me.’ [Hums the chorus.] I think that’s, like, a classic pop record. . . . I can now see now that me even mentioning the words ‘Human League’ would send him off in the wrong direction.”

Shifting to “Don’t Be Careless Love”, a song that explores different sort of territory than “That Day Is Done”:

Costello summarizes the song well in Unfaithful Music:

“One of the most beautiful melodies that he had brought to our writing sessions and into which we had inserted the horrifying images of a nightmare. It was probably the weirdest song we’d written together.”

Costello is right about the melody; it’s intricate, comprising multiple sections not dissimilar in feel to a song off of Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys, a favorite album of McCartney’s. At the beginning, it seems as though the song will be about the worries of a man towards his lover. The song then takes the darkest of turns as it turns out that the narrator is the sort that all of us should fear. In the last verse, McCartney and Costello put us back into the thoughts of the narrator who imagines his lover back in bed with him even though she has been brutally murdered. The narrator finds solace in these imagined thoughts as Paul and Elvis sing, “But in the dark your mind plays funny tricks on you.” It’s a funny line for those with a dark-as-coal sense of humor. Pairing this tale with such a gorgeous melody is the work of two songwriters who are willing to defy convention.

“My Brave Face” is a different song entirely and one in which the duo take convention head-on:

It’s a big song with gigantic Beatles-esque harmonies, incorporating lyrical flourishes such as “Unaccustomed as I am” and “Ever since you went away / I’ve had the sentimental inclination” that match the purest of pop melodies. The demo of “My Brave Face” feels as though it could fit comfortably in the running order of Rubber Soul. Costello and McCartney both considered how the songs that they were composing inevitability sounded like music from Paul’s past. Costello wrote the following on the subject in Unfaithful Music:

“If someone had turned up to write songs with me and tried to get me to rework ‘Alison,’ I’d probably have chased them out the door, but as half the world’s songwriters had gleefully plundered The Beatles’ musical vocabulary, I couldn’t see why Paul should have to go out of his way to avoid it.”

In turn, McCartney commented to Rolling Stone that he followed Costello’s lead when confronted with this inescapable creative decision:

“[Costello] really drew me a bit towards the Beatles thing. He made me think, ‘Why am I being resistant to it? What is the resistance?’ You know, you don’t want to be seen to be trying to be a Beatle again. It is not seemly.”

“My Brave Face” would be the lead single off of McCartney’s next album after writing songs with Costello, and the song received the complete studio attention thought to be appropriate for a Paul McCartney single. Comparing the original demo with the finished product, one can hear the freshness of the duo recording. The immediate rush that both feel is evident, singing and emoting with the knowledge that they have just composed a song equal to any produced by the most popular band in pop music history.

Moving from Beatles Land of “My Brave Face”, the next song — “Playboy To A Man” — finds us back in Costello Country:

It’s an accusation song, directed at first to the woman who dares to “turn you from a playboy into a man,” but then there’s a shift on the part of the narrator and the indictments are hurled inward at himself. Within the text of the song, we see the evolution of the narrator and, in fact, witness the progression from playboy to man. The looseness of the performance in the demo is on display as Costello laughs as they sing the line, “So there you are with your gold chains jangling,” not able to suppress his amusement at this narrator that the duo have created. The discipline of the songwriting approach is apparent within “Playboy To A Man” as there is a set cadence to the lyrics to fit the melody. In Unfaithful Music, Costello writes about he came to accept this adherence from McCartney:

“One lesson that I learned from writing with Paul was that once the melodic shape was established, he would not negotiate about stretching the line rhythmically to accommodate a rhyme…I cheat shamelessly. The unevenly proportioned lines of my early songs drove The Attractions mad. They were difficult to memorize, as no two verses were exactly alike.”

The loose feeling of the demos continues with “I Don’t Want To Confess”:

Neither artist returned to this song in any of their subsequent albums, but the demo recording is endearing as the fun they are having is obvious. McCartney counts off the song and issues a directive to Costello just before the pair sing together. Along with an acoustic guitar, the other instrument may be a ukulele or a guitar in a different tuning. The song doesn’t include a twist as in some of the other McCartney-Costello compositions, but there is still an advancement in the narrative. A line early in the line asks the question, “What happened to keeping them guessing?” By the end of the song, the narrator is instead declaring, “I’m determined to keep them guessing.” He knows how the other person in the song is answering his earlier questions, and his confusion has turned to resolve. The recording ends with a bit of laughter, finding amusement in the odd instrumentation, the audacious harmony on the final chord, and the song itself.

“Shallow Grave” is written around a bluesy riff and even has a little guitar solo in the middle that both McCartney and Costello laugh at:

One rewrite to note when Costello recorded the song for 1996’s All This Useless Beauty is a shift in the first verse from “Let me be the one that Jesus saves” to “Let me be the one that fortune favors.” It’s a less provocative line and certainly makes the song less interesting. Perhaps Costello missed having McCartney’s cover for the line. Regardless, the original demo showcases the two songcrafting masters, especially the line, “Throw another clown to the lions / Throw another Joan on the blaze.” Speaking of provocative songwriting, McCartney compared his working method with Costello with his previous and more famous songwriting partner:

“We would write in the same method that me and John used to write. I figured, in a way, [Costello] was being John. And for me, that was good and bad. He was a great person to write with, a great foil to bounce off, but here’s me, trying to avoid doing something too Beatle-y!”

McCartney continued with this line of thinking in another 2017 interview:

“I’ve developed a way of trying to put people at ease that kind of eliminates the vast majority of [dealing with The Beatles’ legacy]. With Elvis, I didn’t need to do it. He’s sensible enough to know that. We’d sit around and talk and have a cup of tea. By the time we got down to songwriting, we knew the deal. We just sat on these couches. Each of us got an acoustic guitar. Sat across from each other. I said to him, ‘The way I’m used to working with a collaborator is really, mainly with John.’ And the way we used to do it is sit opposite like this. And the thing for me that was kind of nice . . . because I was left-handed and he was right-handed, as was the case with Elvis, too, it was as if I was looking in the mirror….The thing about working with John is that we started songwriting virtually together. We had written a little bit separate from each other. But we grew into songwriting together. . . . You know, the bottom line is I’ve never had a better collaborator than John and I don’t expect to. Because we were pretty hot.”

Costello responded to these comparisons with Lennon:

“I was sort of a little startled when [Paul] made that reference. I think it’s more to just try to explain the immediacy of the way we worked rather than put me in the same bracket as Lennon. I don’t see myself like that. In terms of the immediacy and just the musical role.

For “Mistress and Maid,” McCartney brought inspiration to that particular session with Costello as Elvis recalled in his memoir, writing that the song started:

“after Paul brought in a postcard of the Vermeer painting that he’d found, saying, ‘Let’s write this story.’”

McCartney has a long history of songs serving as character studies in the mode of a short story, including “Paperback Writer” and “Eleanor Rigby.” In the case of “Mistress and Maid,” the main character is driven mad by the callousness of her husband, who no longer treats her the same as when they were first together. She imagines the same gestures and acts of love from the beginning of their relationship to eventually happen to other girls in his future. McCartney and Costello once again play off of the first verse, using the same words to advance the narrative. In the first verse, they write, “But where are the flowers that he used to bring?” and later in the song, it’s updated to “And they’ll get the flowers that he used to bring” to reflect her paranoia and rage. This bit of cleverness is paired with another complex melody.

In addition to the 12 McCartney-Costello compositions analyzed in this piece, the pair wrote three additional songs in which both receive songwriting credits. Those songs include “Pads, Paws, and Claws”; “Back On My Feet”; and “Veronica.” Though demo versions of each of those songs exist, none of the demos include both McCartney and Costello. Despite being the junior member of the songwriting team, Costello had the biggest hit of the two with the much-loved “Veronica” which hit No. 19 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.

Even though the strength of their combined compositions is obvious and the joyous musical spirit that is on display in the demo recordings, a Paul McCartney-Elvis Costello joint album was never really considered. That decision seemed to lie with McCartney. In 1989, he cited the media response as one reason:

“At one point we were thinking, ‘Well, this might be the way to go, to do the whole album together.’ But I started to feel that would be too much of Elvis. And I thought the critics would say, ‘Oh, they’re getting Elvis to prop up his ailing career, you know?'”

In 2017, McCartney reflected further on this possibility and thought that the songs that he wrote with Costello constituted one part of the process in making his own solo album, Flowers in the Dirt:

“I didn’t just want to just make an Elvis Costello album. There were other things I was interested in. I also wanted to work with this fabulous arranger, Clare Fischer, which may not have happened if I had been working with Elvis….I wanted some variety.”

Given the benefit of hindsight, Paul recognized the quality of the demos that he produced with Elvis, saying that “the energy and the performances on the demos were better in some cases” than the officially released versions of the songs. Perhaps McCartney should have listened to himself in this 1980 interview in which he talks about the freshness of “doodling” in the demo process:

“But when you do that sometimes you arrive at something that’s even better than really sitting down and laboriously working it all out…Sometimes you can lose a lot of feel doing that…I’ve heard records where I’ve heard the demo that someone’s done and then they go in and do it properly in the studio and it doesn’t sound anything near as good as the demo.”

For his part, Costello was steadfast in maintaining the excellence of the pair’s demo recordings, writing in his memoir that “they remain the most vivid and uncluttered versions of our songs.”

The 12 song sketches show the songs of the McCartney-Costello partnership in their purest form. Paul decided to use these songs in ways to further his own solo career which is obviously his right as an artist. He may have had a belief that he couldn’t have put out an album of acoustic demos in 1987. But why not? YOU’RE PAUL MCCARTNEY. The public would have been thrilled to hear his own version of The Basement Tapes with a dynamic contemporary artist.

Despite the power imbalance in the relationship, Costello holds his own and more so, actively serving as a good collaborator. He guides Paul away from his worst tendencies, pushing him towards his best songwriting mode. Plus, the demo approach doesn’t allow for any musical flourishes. This serves the two artists well, especially McCartney, whose music sometimes suffers from adding unnecessary instrumentation and experimenting with arrangements. The simplicity of the instrumentation in the recordings are an essential part of their appeal as the fun on display with these two men making music together is infectious. Some of the songs could fit snugly into Beatles albums, but instead reveal the perspective of older artists who aren’t in their twenties, writing from a different and perhaps wiser mindset. Citing the first song included in the collection of songs, The Lovers That Never Were is an apt title for the McCartney-Costello collaboration because it’s the great lost album that never was.

Note: With this Spotify playlist, the original demos are included at the beginning of the playlist. A few of the demos have not been officially released by McCartney, so refer to the YouTube links for those recordings. The studio versions of the McCartney-Costello collaborations are included only if they are referred to in the post.

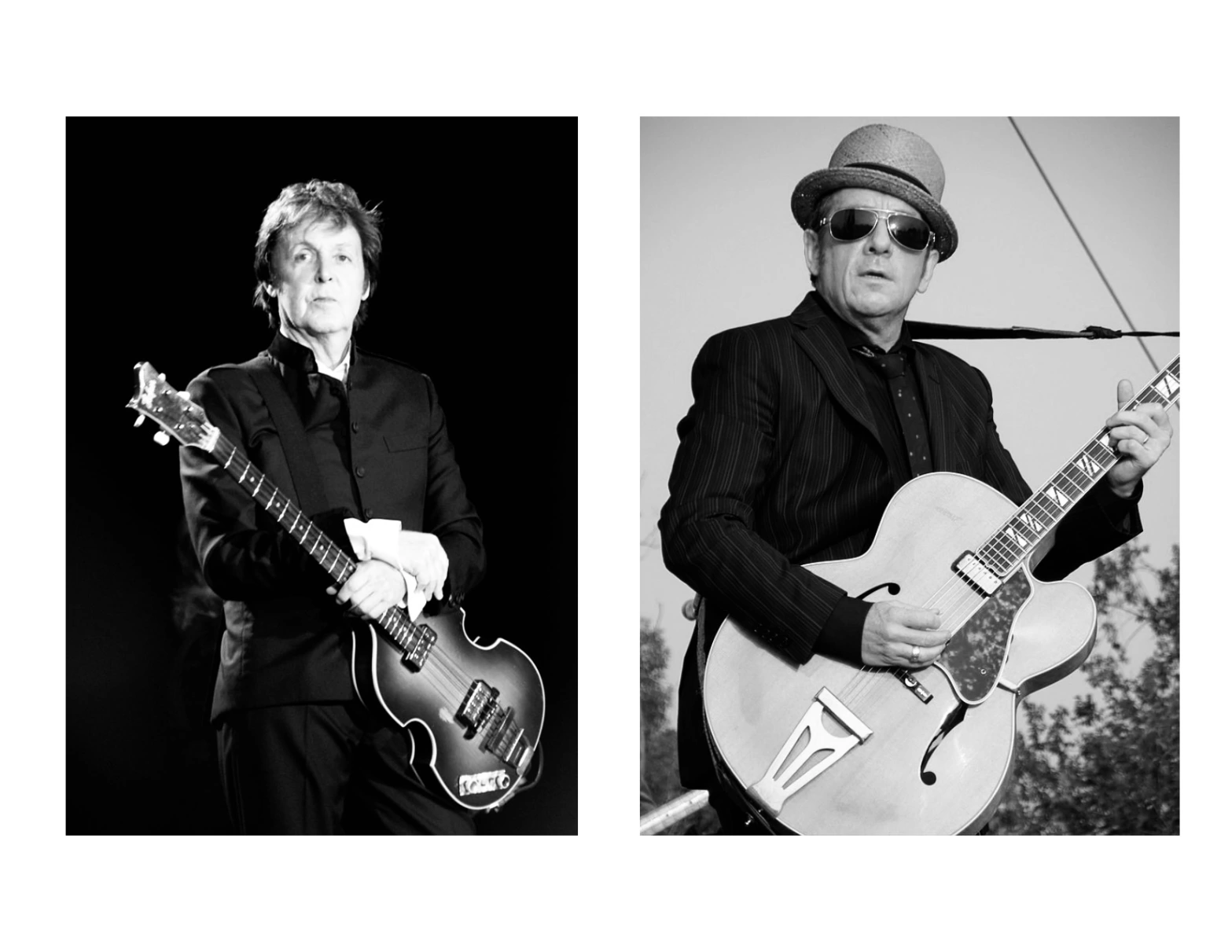

Images: (left) Oli Gill, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons; (right) Robman94, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

I can’t completely explain it, but the harmonies I hear in these tracks put me very much in the mind of the album John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman made together: two sets of roots, intertwining to make some amazing new tree that carries the marks of both sources. Or something like that.

LikeLiked by 1 person