The 1997 album Time Out of Mind was considered a comeback for Bob Dylan, receiving critical praise on the album’s release, which had not been a regular occurrence for Dylan to that point. The album even won multiple Grammys, including Album of the Year. Yet recording the album was not without its disagreements with producer Daniel Lanois, as previously detailed on Recliner Notes. Seeking a trusted keyboard player and an alternative sounding board to Lanois, Dyan brought in legendary musician and producer Jim Dickinson to play during the Time Out of Mind sessions. Dickinson is a secret musical hero primarily known for his varied production credits which include Big Star, The Replacements, Toots and the Maytals, among many others. In 2008, Dickinson was asked about the recording of Time Out of Mind by Damien Love for Uncut. One track that didn’t make the final cut for the album was emblematic of the entire experience for Dickinson:

“[The song] ‘Red River Shore,’ I personally felt was the best thing we recorded. But as we walked in to hear the playback, Dylan was walking in front of me, and he said, ‘Well, we’ve done everything on that one except call the symphony orchestra.’ Which indicated to me that they’d tried to cut it before. I was only there for ten days, and they had tried to cut some songs earlier that didn’t work. If it had been *my* session, I would have got on the phone at that point and called the fucking symphony orchestra. But the cut of “Red River Shore” was amazing. You couldn’t even identify what instruments were playing what parts. It sounded like ghost instruments. And the song itself is really remarkable. It’s like something out of the Alan Lomax songbook, a real folk song.”

Two versions of “Red River Shore” were eventually released on the 2008 collection The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989–2006. The first cut of the song is the one that most reflects Dickinson’s memory of the recording:

While not a symphony orchestra, the whole array of the various instrumentation from Time Out of Mind is evident in this performance. Each verse introduces a different musical instrument. Guitars open the song followed by string bass, drums and Jim Dickinson’s organ, accordion by Augie Meyers, and finally dobro and mandolin. The outro of the song exhibits the classic Time Out of Mind style of all the musicians playing at once.

The instrument that stands out most is Dylan’s voice. Friend of Recliner Notes Robin Dreyer commented on this aspect of “Red River Shore”:

“Dylan alters the melody and his rhythmic treatment of the song with every phrase. He’s ahead of the beat, he’s behind the beat, he drops back and catches up, he changes the notes. It reminds me of Miles Davis playing ballads. It’s a lovely song with some great lines in it, and it’s just a beautiful vocal from a singer whose singing has been ridiculed during his whole career. It’s one of those Dylan recordings that clearly shows that the guy is a musician.”

Robin’s suggestion for a ballad by Miles Davis to consider is “It Never Entered My Mind” off of Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet:

It’s a lovely example of Miles’s playing, deciding when to make a run and adjusting how much of the melody to reveal and how much to lay off. As Robin said, Dylan is doing the same thing with his own instrument by playing with the meter of the words and altering his phrasing within the framework of the melody.

The lyrics of “Red River Shore” tell the oldest of stories, the story of lost love. In the first lines of the first verse, the narrator tells us his mindset immediately:

Some of us turn off the lights and we lay

Up in the moonlight shooting by

Some of us scare ourselves to death in the dark

To be where the angels fly.

These gorgeous lines tell us that this narrator has an affinity for the darkness and a desire to engage with the idea of death; “to be,” as Dylan writes, “where the angels fly.” The narrator also has a way with the ladies:

Pretty maids all in a row lined up

Outside my cabin door.

But they’re not of interest to the narrator:

I’ve never wanted any of ’em wanting me

’Cept the girl from the Red River shore.

This is the introduction of the main subject of “Red River Shore,” the woman who represents the mystery at the heart of the song. In the next verse, the narrator tells the audience about his relationship to this girl:

Well I sat by her side and for a while I tried

To make that girl my wife

She gave me her best advice when she said

Go home and lead a quiet life.

The narrator ignored this plea from the girl as seen by his next words:

Well I been to the East and I been to the West

And I been out where the black winds roar.

The narrator’s roaming and incessant travels to far off places were necessitated by the narrator’s immediate connection to the girl:

Well I knew when I first laid eyes on her

I could never be free

One look at her and I knew right away

She should always be with me.

This connection has a cost for the narrator, a curse from which he can’t escape:

Well we’re livin’ in the shadows of a fading past

Trapped in the fires of time.

The binding curse of the narrator to the past brings us to the heart of the song. The narrator tells us about a land in which even though “nothing looks familiar to me,” it was a place he stayed “a thousand nights ago / With the girl from the Red River shore.” Because of the curse on the narrator to live in the “shadows of a fading past,” he returns to this same place to bask in the memory of the girl since he can’t be with her. The narrator is in for a surprise as “Everybody that I talked to had seen us there / Said they didn’t know who I was talkin’ about.” The narrator doesn’t comment on this curiosity, but continues on with the song. But for the audience, these words begin to call into question the nature of the girl from the Red River shore as well as the reliability of our narrator. These mysteries are further compounded in the final verse:

Now I heard of a guy who lived a long time ago

A man full of sorrow and strife

That if someone around him died and was dead

He knew how to bring him on back to life

Well I don’t know what kind of language he used

Or if they do that kind of thing anymore

Sometimes I think nobody ever saw me here at all

’Cept the girl from the Red River shore.

At the beginning of the verse as the narrator shares about a powerful man who can bring an individual back to life, the inference by the audience is that the narrator wants to bring back the girl from the Red River shore. It would make sense with what we’ve learned from the rest of the song as the narrator feels cursed to live in the past, forever yearning for the type of lost love that can never come back. But with the last lines, the stability of our understanding of the song changes as the narrator says: “Sometimes I think nobody ever saw me here at all / ’Cept the girl from the Red River shore.” Is the narrator the one who needs to be brought back to life? Is the narrator himself the one who is speaking from beyond the grave? If so, it would connect back to the opening of the song when the narrator says that “Some of us scare ourselves to death in the dark / To be where the angels fly.” The narrator and the girl are ghost lovers. He is forever cursed to be haunted by her memory and never truly comprehend his own fate.

“Red River Shore” is a song of mystery. The spookiness inherent in the song’s story enables Dylan to present a deep sense of longing. The only way he can truly capture this emotion of regret is through the telling of a ghost story. This approach is matched in the musical accompaniment as seen through Dickinson’s description of the musicians making music with what sounded like “ghost instruments.”

There have been other songs with narrators speaking from beyond the grave, such as “Long Black Veil,” which was originally recorded by Lefty Frizzell and later covered by The Band. Dylan wrote the deeply chilling “Seven Curses” in which the narrator could be imparting the seven curses on the judge who betrayed her and her father after taking her own life. Dylan is a much older man by the time he writes and performs “Red River Shore” than the 22-year old young adult who writes “Seven Curses.” Dylan has had a lifetime of regrets and personal loss which enables him not only to write a song such as “Red River Shore,” but also to bring all of those emotions as part of the performance to truly embody the voice of the narrator.

In his quotation about “Red River Shore” above, Dickinson hints that Dylan and Lanois attempted many arrangements of the song during the Time Out of Mind sessions. A second version was also released as part of The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989–2006:

In this version, Augie Meyers’ accordion is at the forefront from the very beginning of the song. Dylan embraces a border feel as he has at other moments in his career, so much so that it would fit comfortably on an album by the Tex-Mex supergroup the Texas Tornados. The Tornados included Flaco Jiménez, Doug Sahm, and Freddy Fender along with Augie Meyers himself, whose accordion is at the center of their sound. A good example of their work is “Soy San Luis” from their 1992 debut album:

Considering that Dylan took a Tex-Mex approach for one version of “Red River Shore” and also attempted a ghost-story-told-around-a-campfire arrangement, one wonders about the origins of the song. Because of Dylan’s abiding connection to old music, he must be drawing from the ubiquitous cowboy ballad “Red River Valley”, at the very least for inspiration of the place name at the center of the song. According to Wikipedia, a recording of the ballad by Hugh Cross and Riley Puckett “was the very first commercially available recording of this song under its most familiar title, and was the inspiration for many of the recordings that followed.” “Red River Valley” was sung by Henry Fonda in the 1940 film The Grapes of Wrath as well as Woody Guthrie, Bing Crosby, and hundreds of different artists. But when we’re talking about cowboy ballads, we should hear from the Singing Cowboy himself, Gene Autry:

Dylan doesn’t draw direct lines from “Red River Valley” when composing “Red River Shore” as he would in his sampling method later in his career, but one can see parallels between the two songs. In “Red River Valley,” the narrator shares a similar sense of longing and heartbreak as the narrator of “Red River Shore.” In “Red River Valley,” he says:

Do you think of the valley you’re leaving?

O how lonely and how dreary it will be

Do you think of the kind hearts you’re breaking?

And the pain you are causing to me.

The ghost-like, beyond the grave perspectives of “Red River Shore” can also be seen in “Red River Valley” as the narrator from the latter song says the following:

They will bury me where you have wandered

Near the hills where the daffodils grow

When you’re gone from the Red River Valley

For I can’t live without you I know.

The popularity and seeming omnipresence of “Red River Valley” inspired Johnny Cash to record his own version of the song, titled “Please Don’t Play Red River Valley”:

Neither “Red River Shore” or “Red River Valley” specifically mentions where this “Red River” is located. There is speculation by Canadian folklorist Edith Fowke that “Red River Valley” has its origins in Canada, leading her and others to think that the song is an allusion to the so-called Red River of the North. Because of the use of Gene Autry’s recording in the 1936 Western Red River Valley, many began associating the song with the Red River of the South, which marks the border between Oklahoma and Texas.

For Dylan’s “Red River Shore,” there are not any lyrical clues as to the location of his song. Certainly the Tex-Mex approach in the second version of “Red River Shore” makes one wonder if Dylan is placing the song at the Red River of the South, but knowing that the Red River of the North originates in Dylan’s birth state of Minnesota, perhaps he leaned towards closer waters to home when composing the song. But then, there are Red Rivers all over the world, so maybe Dylan applied the universality of the location purposefully so that the listener can associate the song with their own personal Red River.

“Red River Shore” was recorded during the Time Out of Mind sessions. Dylan utilized an idiom for the album title, which means: “The distant past beyond anyone’s memory.” This definition evokes the story in “Red River Shore” of the ghost lovers, who no one can quite remember. Even the instruments backing Dylan in the song have a spectral feel of the distant past. In a sense, the song is the ultimate realization of Dylan’s concept for the Time Out of Mind album.

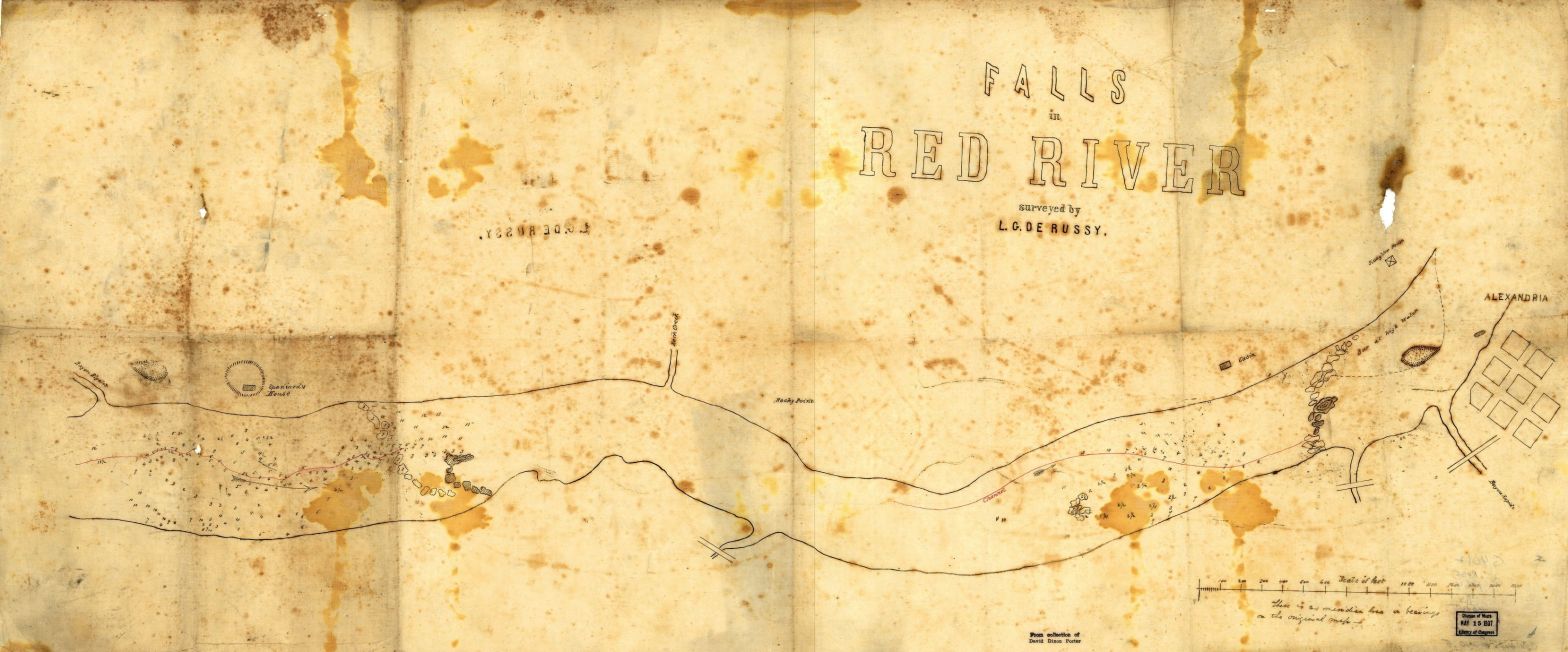

Image: De Russy, Lewis G. Falls in Red River, surveyed by L. G. De Russy. [S.l. ?, 1864] Map.

Certainly one of the greatest masterpieces of Dylan’s career.

LikeLiked by 1 person

wonderful essay– capacious far-ranging exacting, intertextaully worthy of such a muse-love masterpiece

LikeLiked by 2 people

Are you aware of the Kingston Trio’s song with the same name?

I don’t think Red River Valley, even Guthrie’s version has anything to do with Dylan’s masterpiece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am aware of the Kingston Trio song. Though you’re right that “Red River Valley” is probably not a direct inspiration for “Red River Shore,” the song is so ubiquitous and enduring that it can’t help but be in Dylan’s mix of sources.

LikeLike

There is a 1953 movie calledRed River Shore. The female lead looks like Echo Halstrom.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_River_Shore

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good connection and a tantalizing possibility!

LikeLike

Now I heard of a guy who lived a long time ago

A man full of sorrow and strife

That if someone around him died and was dead

He knew how to bring him on back to life

Surely this is a reference to Jesus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great call!

LikeLike

Been following Dylan since the 60’s. Purchased all his albums, including all bootlegs. Was buying his recorded live bootlegs songs, from a bootlegger, during the Larry Campbell, Bucky Baxter, Charlie Sexton, Tony Garnier era, until he was caught and jailed. This by far, is the best Dylan song, I ever heard. My research reveals, Dylan didn’t write the song, Jimmy Lafave did?

LikeLike

Oops! My bad. Jim Lafave recorded and only sang the song. Of course Dylan wrote it. Went back to my research on Bootleg Volume Series #8 (Tell Tale Signs) and confirmed it. SHAME ON ME!

LikeLike