On November 20, 1973 at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, Neil Young and his backing band The Santa Monica Flyers performed a rendition of “Tonight’s the Night” for 34 minutes and 53 seconds. That night in Chicago was the penultimate concert of the tour which had started in Toronto on October 29, moved on to Great Britain for seven performances, and then returned to the United States for five shows. The setlists for these concerts were dominated by a group of songs that Young and The Santa Monica Flyers — a band name adopted for this tour only — had recorded in Los Angeles in August and September of the same year, but which had not yet been released to the public. The centerpiece song for the tour was “Tonight’s the Night,” which was regularly performed twice and sometimes even three times a night. After hearing a batch of unfamiliar songs during this tour, restless audiences would clap enthusiastically when Young would say, “Here’s a song you know,” and then he would begin playing “Tonight’s the Night” all over again.

On that November night in Chicago, Young and the band had already played “Tonight’s the Night” along with three other as-yet unreleased songs from the same recording sessions. The rest of the show consisted of an array of songs, ranging from his work with Crazy Horse to Buffalo Springfield to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (CSNY) and his solo releases. Only one song was played that night from Harvest, Young’s smash hit album from the year before. The concert was not without incident. As recounted in Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography by Jimmy McDonough, Young apparently got fed up with commentary from the audience and yelled:

“Shut up! Some of you people are fucked! You all scream out so much, why don’t you stay home and listen to yourself talk. There’s a lotta things you can say up here if you don’t have to fight your way through a buncha editors that are just yellin’ to hear their own voices.”

The final song of the evening was a reprise of “Tonight’s the Night.” Lasting nearly as long as an episode of prestige television, the performance is equal parts punk, glam, dirtbag, roadhouse, and no wave. This rendition “Tonight’s the Night” is an exhausting yet exhilarating document of an artist who produces a rejoinder to the audience members, a wake for friends who left too soon, and a celebration of simply being alive.

The scratchiness and low fidelity of the recording is apparent from the beginning as the crowd claps and weird guitar noises float over top. Ralph Molina, the drummer for The Santa Monica Flyers, pounds out a slow, deliberate rhythm on the bass drum. Molina was a founding member of Crazy Horse, whose future at the time of the concert was in doubt because of the death of friend and fellow band member guitarist Danny Whitten. Whitten died the year before of an overdose after Young fired him due to his inability to actually play guitar during rehearsals for Young’s large, post-Harvest tour. Whitten was not able to perform because he was in withdrawal from a severe heroin addiction. Young gave Whitten $50 and a plane ticket back to Los Angeles and later that night received a phone call from the coroner reporting on Whitten’s death. His death happened almost exactly a year before the Chicago performance of “Tonight’s the Night.”

As Molina is thumping his bass drum, Billy Talbot joins with single notes on his bass guitar. Young addresses the audience by saying, “Everything is cheaper than it looks, ladies and gentlemen.” Someone close in proximity to the taper laughs in response. Throughout the 1973 tour with The Santa Monica Flyers, Young typically started the show by saying, “Welcome to Miami Beach.” A cigar store Indian and a fake plastic palm tree adorned the stage. To illuminate this part of the set, Young instructs the lighting designer, “Let’s have a little sun on that palm.” The crowd goes nuts, demonstrating that, despite whatever ugliness had happened earlier in the night between the audience and the featured performer, Young is in full control.

Weird effects are played by Nils Lofgren, the guitar player for The Santa Monica Flyers. Lofgren, who would later have his own successful solo career and join Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band as a member, had befriended Young a few years before, contributing to the 1970 album After the Gold Rush. About the 1973 recording sessions and subsequent tour, Lofgren told Rolling Stone in 2023: “It was a healing, commiserative experience since we were trying to deal with the fact that all our friends and heroes were starting to drop dead.” Lofgren is indicating the recent deaths, not only of Whitten, but also Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix.

Lofgren starts playing blues licks as Young introduces the song by saying, “It’s a song you’ve heard me play. I’m going to do it for you right now.” At this point, Lofgren is accompanied by Ben Keith on pedal steel guitar, and they play a strange and brief duet. Young had met Keith in 1971 in Nashville during recording sessions for what would become Harvest. The two became fast friends and Keith would continue to be a musical partner to Young in a variety of projects and genres, usually providing a lonesome, wide-open western skies sound as heard on “Out on the Weekend.”

The showcase for Lofgren and Keith quickly turns into a trio as Young joins them on piano, his instrument of choice for every performance of “Tonight’s the Night” during the 1973 tour. At 1:09, Talbot plays the descending bassline for the first time, the central instrumental motif of the song. The band continues to play a one-chord vamp, cueing off of each other with multiple variations, and producing a glorious cacophony of noise. The heretofore unmentioned member of The Santa Monica Flyers is Jose Cuervo and his tequila. According to one story in Shakey, the mood for the 1973 recording sessions was set by Keith, who screwed off the top of a tequila bottle, threw it away, and yelled, “We won’t be needing that anymore.” That same spirit continued throughout the tour with the band juicing up on tequila and Young apparently drinking it by the wine glass. Despite the mind-altering amounts of alcohol, this whole-band improvisation — riffing off each other, raising and lowering the musical dynamics accordingly — demonstrates that each member of The Santa Monica Flyers is in lockstep after playing together for months.

At 2:53, Young begins singing and repeating the title phrase, “Tonights the night.” A few people in the audience clap, recognizing the song from earlier in the night. Soon, Molina and Keith (and maybe Talbot) join in and harmonize with Young followed by the infamous descending bassline. Young and the band clearly love playing this song and can and will play it all night. At 4:00, the band dramatically downshifts the tempo as Young sings the first verse:

Bruce Berry was a working man

He used to load that Econoline van

A sparkle was in his eye

But his life was in his hands.

A few months before The Santa Monica Flyers’ recording session in August and September 1973, Bruce Berry died of a heroin overdose. Before his death, Berry had been a roadie for CSNY and was a member of Young’s inner circle. It was Whitten himself who had introduced Berry to heroin, starting the latter’s addiction. Berry’s overdose — along with Whitten’s death the previous year — inspired the composition of the song. Bruce Berry was no stranger to rock ‘n roll as he was the brother of Jan Berry, one half of the famed singing group Jan and Dean. Along with the early Beach Boys, Jan and Dean were known for their surf/beach/cars/girls utopian visions, best expressed in the song “Surf City,” co-written by Beach Boy Brian Wilson:

Featuring the transcendent California prophecy, “Two girls for every boy,” it was the first surf song ever to reach the #1 spot on Billboard’s Hot 100 the week of July 20, 1963, almost exactly 10 years before the recording of “Tonight’s the Night.”

The life story of Bruce Berry’s brother Jan’s is itself fascinating. Jan and Bruce’s father worked for Howard Hughes as a project manager for the “Spruce Goose” and flew on its only flight with Hughes. After producing a string of hits, including “Drag City” and “The Little Old Lady from Pasadena,” Jan and Dean’s run at the top was over after a car accident left Jan with severe head injuries, resulting in brain damage and partial paralysis. Ironically, Jan’s accident occurred a short distance from Dead Man’s Curve in Beverly Hills, two years after the duo’s 1964 racing nightmare song, “Dead Man’s Curve”:

The song features the following spoken-word recitation:

Well, the last thing I remember, Doc, I started to swerve

And then I saw the Jag slide into the curve

I know I’ll never forget that horrible sight

I guess I found out for myself that everyone was right.

This passage ends with a three witches from Macbeth-type warning: “Won’t come back from Dead Man’s Curve!” The a cappella harmonies sound eerily similar to the harmonies when The Santa Monica Flyers sing the title phrase of “Tonight’s the Night.” Jan himself struggled with addiction after his crash and Bruce’s death.

Back to Chicago 1973, Young continues singing about Bruce:

And people, let me tell you

Late at night when the people were gone

He used to pick up my guitar.

Young pauses his singing and allows Lofgren to take a short guitar solo. Young does this every time he and The Santa Monica Flyers perform “Tonight’s the Night” on the tour, demonstrating his respect for Lofgren’s talents as a guitar player. Young then sings the remainder of the verse:

And sing a song in a shaky voice

That was real as the day was long.

It’s curious that Young describes Bruce as having a “shaky voice” whereas his brother Jan’s voice was decidedly not shaky. Apparently, Bruce did not share the smooth, archetypal Californian sunshine vocals DNA with Jan.

After finishing the verse, Young and The Santa Monica Flyers move back to the chorus. In between each invocation of “Tonight’s the night,” Young inserts a different piano lick. Young’s piano playing is part honky tonk, part Jerry Lee Lewis glissando, and part lunatic. After the chorus, Young sings the second verse of the song:

Early in the morning at the break of day

He used to sleep until the afternoon

If you never heard him sing

I guess you won’t too soon

‘Cause people, let me tell you

It sent a chill up and down my spine

When I picked up the telephone

And heard that he’d died out on the mainline.

Counting Danny Whitten, this was the second time that he had picked up the telephone and been informed of an overdose of a close friend in a year. These deaths couldn’t help but inform Young’s songwriting and the atmosphere recording the songs in August and September. According to Lofgren in Shakey:

“The mood was hangin’ in the air. You could cut it with a knife. There was no need for Neil to lead us to the mood. We were all affected in our own ways by Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry dying. That’s what that whole record was about — we didn’t sit around and talk about ‘Oh God, what a shame.’ This was a chance for all of us to come together and get out of that stuff.”

Did this feeling extend to the fall 1973 tour? Again, here’s Lofgren in Shakey:

“The mood live was completely different. There was an angry edge the original recording didn’t have. We were all pissed off about losin’ a couple of people close to us and it came out.”

After the end of the second verse, The Santa Monica Flyers play an aggressive, instrumental section which is punctuated by Young pounding out licks on the piano, illustrating the angry edge described by Lofgren. Young then sings about Bruce and his Econoline van once again, and, at 6:56, he reaches the line, “A sparkle was in his eye.” Young repeats the phrase a number of times, as if to consider Bruce’s sparkling eyes from different vantage points. Lofgren plays off of Young’s vocal, ad-libbing with his own improvisations. The notes that Young sings in this segment recall a portion of “Last Dance,” a song that Young sang earlier in the year:

This recording of “Last Dance” is taken from a performance at the San Diego Sports Arena on March 29, 1973. This tour was also a nightmare as Whitten had died during rehearsals and was subsequently plagued with bad vibes from the audience, bad moods from the band members who insisted on more money, bad sound as Young couldn’t keep his guitar in tune, and bad singing with Young losing his voice halfway through the tour. It was an all-around terrible environment for everyone involved. Young released the album Time Fades Away, featuring recordings from the tour to document the entire experience.

“Last Dance” is the last track on Time Fades Away and is a forceful yet haunting song. At the 5:00 mark of “Last Dance,” Young can be heard in the middle of a reverie about waking up and getting ready to go to work. He sings that the sun has been up for “hours and hours.” He continues:

Well, you light up the stove

And the coffee cup is hot and the orange juice is cold, cold, cold

Monday morning, wake up, wake up, wake up.

The notes that Young sings in this passage are the same notes he sings during the repeated “A sparkle was in his eye” in Chicago only eight months later. Besides sharing the same unsettled, wobbly, and improvised melody, the two performances are linked in another way as will be demonstrated later in this post.

Back to “Tonight’s the Night”; at the 7:27 mark, Young begins repeating the phrase “late at night when the people were gone.” He screeches the line a few times and even says at one point, “Late at night when no one was in the arena.” Young seems to be taunting the audience, implying that maybe they should go ahead and file out of the arena. With this touch of hostility and his piercing vocals, Young would never adopt this vocal delivery again after the 1973 tour, reinforcing his subsequent comments that, throughout this time period, he was inhabiting a persona. As Young told interviewer Bud Scoppa in 1975:

“I was able to step outside myself to do this record, to become a performer of the songs rather than the writer. That’s the main difference – every song was performed. I wrote the songs describing the situations and then I became an extension of those situations and I performed them. It’s like being an actor and writing the script for myself as opposed to a personal expression. There’s obviously a lot of personal expression in there but it comes in a different form, which makes it seem much more explicit and much more direct.”

Young expanded on this idea during an interview with McDonough for Shakey:

“But I did get into a persona. I have no real idea where the fuck it came from, but there it was. It was part of me. I thought I had gotten into a character — but maybe a character had gotten into me.”

At 8:03, Young once again sings, “He used to pick up my guitar,” causing Lofgreen to go off by himself as he alternates between a machine gun’s flurry of notes and holding a single note that sears and soars. From this, Lofgren fluidly transitions to a new riff that sounds remarkably similar to “Crossroads” by Cream from 1968’s Wheels of Fire. This is the kind of song that a 17-year old wannabe guitar hero like Lofgren would have been obsessed with at the time of Wheels of Fire’s release:

The rest of the band joins in with the “Crossroads” riff as Young takes the lead with some demented honky tonk piano. This stretch of music is extraordinary, though it’s hard to make out much. Keith can be heard letting out a few lonesome whistle moans on the pedal steel. At 10:12, Young sings the first verse once again with Lofgren adding a curious glimmering sound on guitar in response to the line “A sparkle was in his eye.” Perhaps sensing that Lofgren is playing with extra juice that night, Young sings the cue for another Lofgren solo spotlight. This time, the rapid fire assortment of licks that Lofgren offers up includes a quick taste of The Allman Brothers Band’s live performance of the Sonny Boy Williamson II song “One Way Out” off of Eat a Peach, released the year before the 1973 Santa Monica Flyers tour:

Eventually, Young joins in with Lofgren for a piano and guitar duet. Young soon drops out as Lofgren continues to play riff after riff. The audience, perhaps in recognition of how special the playing is, claps along to Lofgren’s stylings. Young softly sings phrases into the microphone. It’s as if Young is a mumbling drunk at the bar who keeps repeating the same things to himself. Everyone at the bar tries to ignore him, but then he utters something that cuts through the haze and forces the others in the bar to pay attention. At 12:30, Lofgren plays a weird, descending figure that sounds like a cartoon sound effect of someone falling down. Talbot answers by playing the main bassline, but The Santa Monica Flyers don’t move to the chorus. They vamp on a single chord, allowing Young to softly share memories of Bruce Berry. When Young sings, “He used to sleep until the afternoon,” the band expects that they will finally break into the chorus and play the transition fanfare to announce it, but Young has other ideas. Instead, he sings “He’s tired,” repeating it twice more, the last time extending the last note to a breaking point — “tiiiiiiiiiiiiiii-red.” This phrase is not in the recorded version of “Tonight’s the Night,” so it’s an improvisation by Young and could be a reference to “Tired Eyes,” another new song which had been recorded on August 26, 1973:

As previously explored on Recliner Notes, “Tired Eyes” was inspired by a drug deal gone bad that resulted in the death of four people in Young’s former hometown of Topanga, CA. Though not directly about the deaths of Bruce Berry or Danny Whitten, the song captures the dark vibes emanating from Topanga Canyon. Only a few years before the song, the place had the feeling of a hippie utopia, but now that vision is shattered for Young. He and The Santa Monica Flyers plead throughout the song, “Please take my advice / Open up the tired eyes.” It could be an appeal to the four dead men, hoping beyond hope that they aren’t truly dead. Or, the words could be self-addressed, an attempt by the song’s narrator to jar himself out of a self-imposed cloud of booze and drugs. Another interpretation is that Young and his band are singing directly to the listener, beseeching them to truly look at the state of the country around them and the collective desperation and deep need for compassion and love. “Tired Eyes” is an intense and forlorn cry for help by Neil Young.

At 13:32 of the “Tonight the Night” recording, Young and The Santa Monica Flyers break into the chorus once again. As the band plays and harmonizes repeatedly on the title phrase, Young interjects atonal phrases similar in sound to the “hours and hours” section previously noted from “Last Dance.” Young’s utterances include: he’s tired; Bruce Berry was a working man; he used to play guitar; he used to load the Econoline van; he used to put the strings on my guitar; used to tune the guitar; he used to wait for me there in the hallway.

Soon, the band stops playing their instruments and repeats the title phrase a cappella with Young continuing his rap. According to a quote in Shakey from Tim Foster, one of Young’s technicians, this mode reflects the origins of the song:

“They started workin’ this thing out a cappella, everybody sitting around thumping the tables. The next day, Neil shows up with all these lyrics about Bruce Berry.”

It’s no surprise that the inspiration for the song came from the members fooling around with singing harmonies since Crazy Horse had originally started as a singing group called Danny & the Memories. The core of that group was Whitten, Talbot, and Molina:

Despite the pervasive gloom within a story littered with death and heartbreak, the genesis of so much of this music can be traced back to singing groups from the early 60s such as Jan and Dean and Danny & the Memories. The pull of creating vocal harmonies is powerful for The Santa Monica Flyers with the simple act of singing together resulting in the composition of “Tonight’s the Night.”

With the a cappella harmonies repeating in the background and Molina’s bass drum thumping single beats, Young begins a long monologue around 15:20. Sometimes he talks about Bruce and continues to share his story with the audience, while other times Young directly addresses him. The audio of the recording is not clear enough to catch everything, but he talks about how “Days were good” going around the United States, “Traveling from town to town.” Then Young mentions something about James Brown and “his famous band.” Chalk it up to another example of Young’s dry Canadian irony as he compares himself with the Godfather of Soul and The J.B.’s with The Santa Monica Flyers. The rap continues with Young saying, “I don’t want to play it until you tune it. Just tune it, Bruce. Tune my guitar right up.” Fans in the audience can be heard talking back to Young. They could be yelling in anger or trying to provide encouragement or both. The monologue continues:

“They can’t play it themselves, you know what I mean?…You know, times are changing…Time for us to get off the road…We’ve been together too long, man…Bruce, you’ll be without a job for a little while, only for a couple of years, you know, man? It’ll be alright….I don’t know man. Let’s do one. Do one for Stephen, man.”

Young is referring to Stephen Stills, another member of CSNY whom Bruce Berry would have worked for as a roadie as well. While the others continue their repetition of the title phrase, Young intersperses piano runs within the monologue as the off-rhythm or atonal sounds trade off with twinkling flourishes. The rap changes as Young shares a story about Bruce and David Crosby of CSNY, who had left his guitars in Berry’s care. Crosby succinctly told the story in Shakey:

“[Berry] came back one afternoon and said, ‘Hey, somebody broke into the trunk of your car and stole your Stratocaster.’ Well nobody had broke into my car. Bruce had stole it for junk.”

Young shares this same story during performances of “Tonight’s the Night” throughout the fall 1973 tour. Usually, the anecdote is told in the form of a two-person play with Young performing both parts, improvising the dialogue so that it is slightly different from night to night. On the night of November 20, Young delivers the story as a one-sided perspective from Crosby’s point of view:

“What happened, Bruce? What happened to my guitar, man? I mean, I left it in the station wagon. My guitar, man, what happened to my guitar, Bruce? What do you mean, you lost my guitar, man? What happened? You lost it, man, you lost my ax, man…[unintelligible] a courtesy. Get it this second. I can’t get my ax, man, and now it’s gone…I can’t get it…I took a chance. There’s something I want to play…[unintelligible]….What happened to it, man? Bruce, where’s my guitar, man? What the hell, will you? It’s time, man. I’m waiting. I’m waiting long. They’re waiting, man.”

With that, there’s a bit of applause from the audience since Young has recognized them as participating in this little play. Young begins emphatically saying, “No.” He repeats it again and again: “NO. NO. NO.” Though this part is spoken by Young, this stretch of repeated “no”s recalls the ending of “Last Dance” when Young and the band on that recording repeatedly sing, “No no no.” In “Last Dance,” the overwhelming negation serves as a communal act, coming together to reject everything, similar to what would happen in the punk movement only a few years later. As Greil Marcus may have once said about punk, “A thousand noes would add up to one big yes.” The negation within “Tonight’s the Night” on November 20, 1973 is of a different sort of gesture. Young implores, “No” to fight off everything he knows. He is playing a character on this tour and also playing a character within this little play. None of these characters want to face the reality of what Bruce Berry has become; someone who would steal from an employer and a friend to feed his addiction. This isn’t a recognition of community through negation as in “Last Dance” or punk but rather a personal desire to change certain outcomes and realizing it is out of his control.

As Young yells, “NO,” he hits single notes on the piano. After a few more “no”s, he moves beyond single notes to dissonant chords. The piano is either a voice in the conversation or providing a soundtrack for the dialogue. Soon, a few in the crowd yell back, “Yes!” Young silences them by muttering a line directed at Bruce: “You put it in your arm, man.” This concludes the one-man play within “Tonight’s the Night.” It’s a dark and depressing story shared at a rock ‘n roll concert of all places. In Shakey, McDonough asked Young about the differences between the previous Time Fades Away tour and the fall 1973 tour, and he replied:

“Tonight’s the Night was a lot more fun [than the Time Fades Away tour]. ‘Cause I was with my friends. I was havin’ a fantastic time. It was dark but it was good. That was a band with a reason. We were on a mission. That’s maybe as artistic a performance as I’ve given. I think there was more drama in Tonight’s the Night because I knew what I was doing to the audience. But the audience didn’t know if I knew what I was doing. I was drunk outta my mind on that tour. Hey — you don’t play bad when you’re drunk, you just play real slow. You don’t give a shit. Really don’t give a shit. I was fucking with the audience. From what I understand, the way rock and roll unfolded with Johnny Rotten and the punk movement — that kind of audience abuse — kinda started with that tour. I have no idea where the concept came from. Somebody else musta done it first, we all know that, whether it was Jerry Lee Lewis or Little Richard, somebody shit on the audience first.”

After “You put it in your arm, man,” the harmonies die away except for one voice singing the title phrase. The band starts playing their instruments again. Young sings key lines from the song, but at the 20:10 mark, Young screeches, “Get up at the break of day.” The words in the line contrasts with the emphasis on night in the song’s chorus, but they align with the message in “Last Dance” of waking up in the morning. Beyond the words, it’s the way that Young delivers the line that stands out. His voice is clearly heard on the limited recording. There’s no mistaking the jarring scream that’s harrowing enough to shatter windshields and make the Chicago audience forget about the quiet acoustic songs on Harvest. In an immediate about-face, Young shifts to a different vocal approach, softly singing and almost whispering about sleep. It’s hard for anyone to sleep after the previous shriek, so Young’s attempts seem like a cruel, ironic joke. While this is happening, Lofgren, Keith, or both produce a ringing sound that is straight out of the soundtrack of a hair-raising film noir. It’s fitting because everything that is presented onstage is a suspense film. Young slowly sings about Bruce again. “He was a working man…A sparkle was in eye…His life was in his hand.” His delivery has decelerated from the beginning of the song, affirming Young’s previous quote about slowing down when drinking an excessive amount of tequila.

At 21:08, Young sings the big cue for Lofgren again, banging out a single discordant note with each word running on top of the next: “Lateatnightwhenthepeopleweregoneheusedtopickupmyguitar.” Lofgren wails on the guitar again, but it’s not a solo spotlight this time. Keith riffs away on the pedal steel, supporting Lofgren’s bluesy licks. All of a sudden, the whole band produces a frenzy of sound with Molina playing a driving beat. The mics are overloaded, and the recording is tumultuous, but it’s magnificent. Amidst the harsh miasma, big Neil Young-style notes ring out from an electric guitar. Has he left the piano and started playing a guitar? That must be the case because no one else in the world in 1973 makes that particular electric guitar sound. It’s a wall of sound. Not Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound with an orchestra producing ethereal pop music, but rather as if your car hits a wall and you hear every single inch of the car going through the wall. The noisy wave depicted in the recording comes years before Lou Reed would release Metal Music Machine or the members of Sonic Youth would form as a band. Young himself would embrace this violent style of playing during the 1979 Rust Never Sleeps Tour and especially the 1991 Arc–Weld tour, but here he is with The Santa Monica Flyers producing the sound of a collapsing black hole.

In March 2023, Young appeared on the Conan O’Brien Needs A Friend podcast and shared songs from his youth that inspired him. The final song that he selected was “Bob-A-Lena” by rockabilly artist Ronnie Self:

Young said the following about “Bob-A-Lena”:

”This one, I couldn’t believe. I could pick it up [on the radio], but they seemed to play it at the same time every night. So, I would be in bed and I had my little transistor radio tuned into this and I’d hear this thing. I go, ‘God that is insane! This guy’s nuts!’”

Though the music of “Bob-A-Lena” and “Tonight’s the Night” don’t resemble each other, it’s the sense of abandon that can be heard in the lead musicians that are similar. The two performances are connected in Self and Young’s willingness to renounce status, wealth, friends, and family to reach for something inside a hurricane even though their lives are at stake. Self battled alcoholism for most of his life and died at the age of 43. In 1973, no one was quite sure about Young’s commitment to a future.

At 24:04, the roar stops abruptly. Out of the feedback, Young and company begin repeating the title phrase in harmony once again and Talbot plays the familiar bassline. The crowd applauds the transition. Soon, the musical accompaniment falls away and they’re back to singing a cappella. Young begins moaning, and it’s akin to a dog or a wolf howling at the moon. He starts singing a variety of phrases, including the line, “Baby, baby sing with me somehow.” It’s a sample from one of Young’s most famous songs, “Helpless” off of the 1970 CSNY album Déjà Vu. Young and The Santa Monica Flyers had performed “Helpless” earlier in the night of November 20. An example of the band performing “Helpless” on this tour comes from Somewhere Under the Rainbow, a recording of their November 5, 1973 performance in London:

This beautiful song about memory, childhood, and innocence lost fits quite well as a companion to “Tonight’s the Night.” When Young sings, “Baby, baby, sing with me somehow,” he could be directing the line to the memory of Bruce Berry and Bruce’s tendency to sing “a song in a shaky voice.” Or, Young could be directing the line to the audience themselves, calling on them to sing along with the voices of the band formerly known as Danny & the Memories.

Through all of this, the audience is clapping along to the beat, participating in the spooky ritual. The twinkling piano returns so we know that Young has put away his electric guitar. He murmurs, “Just a little heartbeat.” Is that a comment to describe the piano part he just played or rather an acknowledgement of the crowd’s clapping that provides a heartbeat for the band. Young then says, “Well, let’s hear it from you people; let’s hear it from the front.” The audience whoops in response. He may be saying this in a genuine way, or perhaps he’s ironically working the crowd, playing the part of an entertainer in a cheap night club in Miami Beach. Regardless of Young’s intention, the crowd loves it.

At 26:15, Young bellows a big, “WHOA” which seems to be a signal to the band to end the song. They play a big finish with lots of noise and the audience goes nuts. Of course, it’s a false ending because The Santa Monica Flyers start harmonizing the title phrase once again. A woman laughs on the tape as everyone claps along. A man mutters, “Wow.” He seems to be shaking his head as he says it, in equal parts disbelief and respect that the song is still being played. The band keeps singing a cappella for several minutes accompanied only by Young’s piano. The repetitive nature of the vocal hook from “Tonight’s the Night” recalls another song from 1973, “Show Biz Kids” by Steely Dan off of Countdown to Ecstasy:

The background singers in the Steely Dan song repeat “Go to lost wages,” a purposeful misstating of “Las Vegas.” The rest of the lyrics are a reflection on the haves and the have-nots in American society. As the titular show business kids, “Got the booze they need / All that money can buy” and they’re “Making movies of themselves,” the perspective of the song is abrasive and cynical which differs from the forthright commiseration in “Tonight’s the Night.” However, both songs employ a similar bluesy, repetitive vamp with minimal chord changes; “Tonight’s the Night” utilizes two chords and “Show Biz Kids” only one. The Steely Dan song was released only one month before Young heard The Santa Monica Flyers harmonizing the title phrase in the studio and composed the rest of the song about Bruce Berry. Young may have sought to capture the milieu of “Show Biz Kids” in “Tonight’s the Night,” the same doomed decadence of early 1970s West Coast.

At 28:35, Young once again sings, “Late at night when the people were gone, he used to pick up my guitar,” the cue for Lofgren to play the role of guitar hero one more time. Lofgren doesn’t disappoint, making his guitar seem like it’s crying at the heavens. Young yells something indistinguishable and repeats it in a quieter voice. He plays the piano as an indication for Lofgren to wrap it up. Keith starts shooting his own licks from the pedal steel while Young finds a new groove with the piano. He drops that passage before it can get started to move back to a cappella singing once more. The Santa Monica Flyers join him as does the audience who are clapping again. A woman can be heard saying, “Oh my God.” You’re right, lady, they’re still going. At one point, Young himself sings the song’s descending bassline, not needing a bass to provide the song’s signature musical motif.

At 31:35, Young begins a new rap over the harmonies. At one point, he declares, “Tonight’s the night. It’s kinda hard to memorize,” which receives a few laughs from the crowd. Then he says, “Just think of me as James Brown,” once again invoking “the hardest working man in show business.” It could be a reference to Brown’s infamous onstage cape routine during “Please Please Please” in which Brown appears to be finished with the song and can’t go on while his roadie puts a cape over him. Brown then finds the strength to continue and pushes away the roadie so that he and the band can keep playing. Young knows it’s a funny comparison for him to make since his and Brown’s styles are so inherently different, but to make this comment while in the middle of doing a James Brown bit is so perfectly Neil Young.

The chanting of “Tonight’s the night” repeats on and on. Young encourages the crowd and even goads them, saying “From here on, it’s up to you Chicago” and “We’re having a night of fun.” This Miami Beach nightclub entertainer knows how to work a crowd. He yells, “Let’s hear it!” and then “Louder!” Finally, he pounds on the piano yelling, “WHOA,” the signal to the band to finish the song. They play the big chord and finally, mercifully, end the song. The second performance of “Tonight’s the Night” is over as is the concert. The audience is ecstatic. Maybe there is relief on their part, but it’s easy to sense that they know they witnessed something special. Young thanks the audience twice and says, “We love you. See you in a couple of months.”

Young and The Santa Monica Flyers would only play one more concert together, a few days later at the Community Theater in Berkeley, CA. A hometown gig of sorts since Berkeley is a short drive to Young’s ranch near La Honda, CA. No setlist exists from the concert, but it’s safe to assume that he and The Santa Monica Flyers performed “Tonight’s the Night.” Young would not play the song live again for another five years. One would have expected Young to release the recording sessions from August and September as an album after he left the road, but they were put aside and mostly forgotten for more pressing concerns. More than a year later in early 1975, Young was readying to release a different record called Homegrown. As a way to celebrate, he listened to an early version of the album with a number of friends, including Rick Danko and other members of The Band. The story goes that after the Homegrown tape ran out, the recordings from the August and September 1973 sessions started playing. As recalled by Molina in Shakey:

“Danko freaked. He said, ‘If you guys don’t release this fuckin’ album, you’re crazy.’”

That was enough for Young, who immediately changed course and shelved Homegrown. Tonight’s the Night was released in June 1975, exposing the world to the story of Bruce Berry and the heartbreak of Danny Whitten’s passing. But for the audience in Chicago on November 20, 1973, the story that they would go on to tell about the song “Tonight’s the Night” would be about the extraordinary rendition of the song, performed specifically for them, that stretched out for 34 minutes and 20 seconds. Perhaps in telling that story, each would say what they witnessed: a wake, an exorcism, an occult ritual, a celebration, or maybe a goodbye.

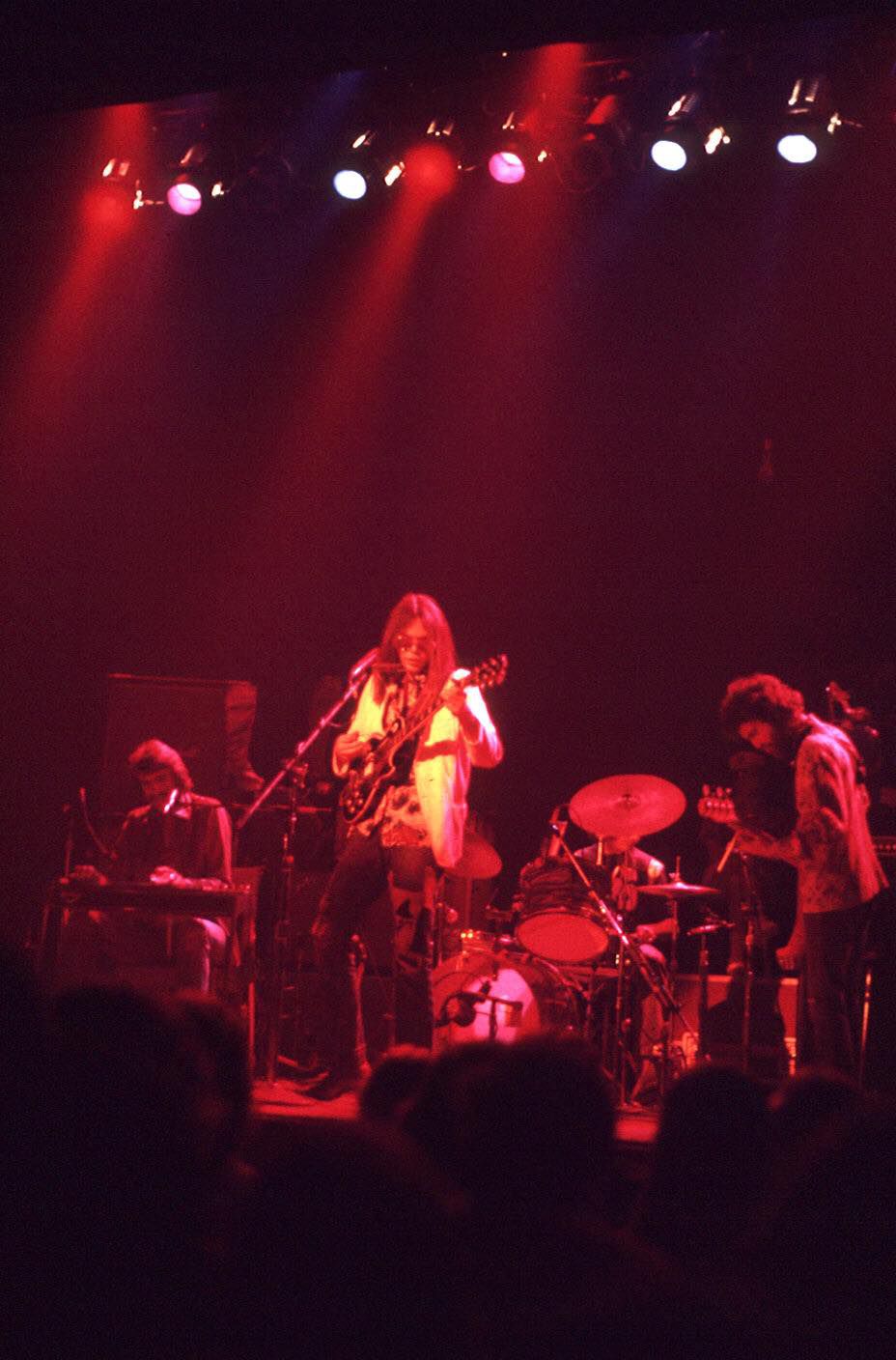

Image: Photo by Ron Draper, 1973-11-23, Community Theater, Berkeley, California, USA, courtesy of Sugar Mountain.

Really great article. Reading it made it feel like being there. Makes my desire to hear the Berkeley show one more time. That’s been my holy grail show to find. Asked Neil on NYA if they taped that show. The only record of it is Ron Draper’s photo. Still hoping it surfaced soneday. Thanks for writing this piece. I hope Neil sees it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and for the kind words! According to Tyler Wilcox (https://doomandgloomfromthetomb.tumblr.com) and who has interviewed folks in the NYA camp, there weren’t any soundboard recordings made of the Tonight’s the Night tour. For Berkeley, you’d have to find an audience tape.

LikeLike

I was at that show in Chicago and it still haunts me. I ran into Neil at a movie theater a couple of years afterward and chatted with him a little bit about the show. He was in a much better place than in 1973.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Do my speculations about the audience response ring true?

LikeLike

Very innaresting! Thanks *Big Time* for posting this!

LikeLiked by 1 person