If on a winter’s night a traveler, the 1979 novel by Italo Calvino, consists of delineated chapters, each of which are divided into two sections. The first section of the individual chapter is a narrative of the reader trying to read a novel called If on a winter’s night a traveler while the second section consists of a completely different story than the previous chapter’s second section. Working through the novel for the first time as a reader can be confusing, jarring, and even frustrating as reading it is an act of beginning a story that gets pulled away just as the narrative is getting good. It’s only after completing the entirety of the book that the themes on the slippery nature of art and life become apparent and the satisfaction of the book takes hold.

The act of listening to “Cliff Dweller Society” by Tortoise for the first time can be a similar experience as reading Calvino’s novel. A musical corollary of sorts to If on a winter’s night a traveler, the 15 minute and 23 second long track can be heard as its own series of beginnings:

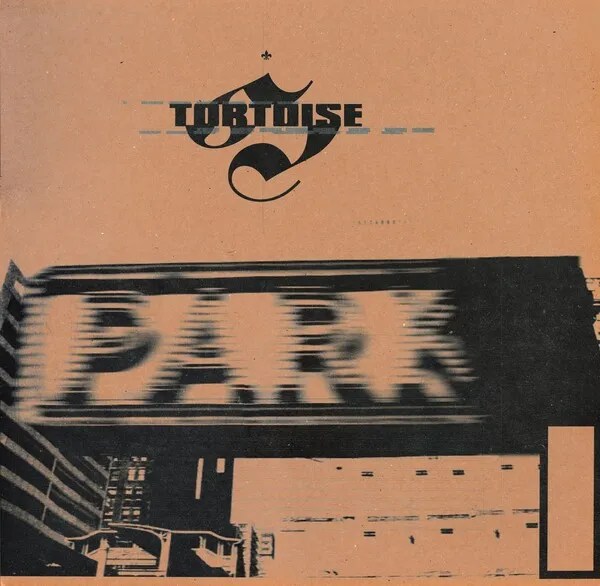

Released by Duophonic Records 30 years ago in 1995 as a 12” single, “Cliff Dweller Society” and its flip side “Gamera” were recorded at a decisive time in the development of Tortoise as both were among the last music featuring the band’s original lineup: Dan Bitney, Doug McCombs, John Herndon, John McEntire, and Bundy K. Brown. Up to this point, Tortoise had issued its first LP —the self-titled Tortoise — as well as Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters, a collection of remixes of the songs that appeared on Tortoise. In a recent interview with Recliner Notes, Brown (who now goes by “Ken”) recalled the context and the instigation for the creation of “Cliff Dweller Society”:

“I think that we were in this interesting point with Tortoise, where the first LP had come out. We had a lot of energy behind us. We were getting a lot of requests to do shows. We had done a few small regional US tours. We were keeping very busy, and we were beginning to write new material. And we had done shows with Stereolab. I don’t recall if John [McEntire] had recorded them yet, but we built up a relationship with them. They had their label, Duophonic, and so they wanted us to record something for them…It was more of a singles label, so it actually fit really well, timing-wise, for us…We were in that arc of we had started some of the material that would end up on [Millions Now Living Will Never Die], but we didn’t have a lot of new material…but we did have this arrangement of ‘Gamera’ that we had been playing live…that’s really an extension of an idea that was on the first album. It’s different enough that it’s its own song. And we said that we’ll figure out what else was going to flesh out the single with from there.”

The “what else is going to flesh out the single” in Brown’s quote would become “Cliff Dweller Society.” The series-of-beginnings nature of the track had its inspiration from a song that Brown and McEntire had created while in their previous band Bastro:

“Some years prior, John and I had made a record with Bastro that was a Sub Pop single, a split single called Bastro And Codeine, and the side two of it was a tribute to the DAF record Produkt. That DAF record…was little snippets, little portraits of different things, some of them sounded improvised. And that’s exactly what we did on the B-side of the Bastro And Codeine thing. It was snippets of pieces and then we edited it all together into one piece. John liked that idea and had remembered it, and he said, ‘Well, why don’t we do something like that? Why don’t we make a collage?’”

“Cliff Dweller Society” is indeed a collage, a pastiche of musical fragments that constantly introduces new ideas without ever resolving the previous ones (barring one big exception).

Breaking down “Cliff Dweller Society” bit-by bit, the actual beginning of the track quickly fades in, unveiling a melodic figure on bass, though it’s barely heard in the background for the sound of supersonic windshield wiper effects in the foreground, whapping back and forth. This small, 10-second slice of music is a perfect way to kick off a song made up of beginnings since it could have been expanded into its own stand-alone piece of music. Instead, it’s over before it has the chance to be built upon. With that, a repeated screeching of static announces the commencement of the next segment as one or two stringed instruments are plucked, the notes of a vibraphone play in an intermittent fashion, and a slightly incongruent whistle sounds off every now and then. A slow and easy yet jagged rhythm emerges, like a lounge act who has been forced to play for 10 hours through the night. Static continues to burst in and out at different points throughout this part as it’s understood that a radio is being played. Voices on various stations come and go. They’re not speaking English. The needle on the radio is being adjusted to try and have any station come in clearly. Somewhat paradoxically, a few of the musical instruments continue to play on and off in the background while the radio slides between stations. The music and voices blink out for a moment to nothing and then flare up again before disappearing to silence.

The radio sound effects in this part of “Cliff Dweller Society” recalls the introduction of “The Match Incident,” Steve Albini’s contribution to Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters in which a person can be heard driving and parking a car, entering their house, and switching between TV channels while Tortoise begins playing in the background. The art of tape editing is central to Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters. Likewise, McEntire and Brown’s love of physically manipulating musical tape was a driving force of Tortoise in this period as Brown noted:

“That was the reference we were making on the Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters cover, that’s the image of John [McEntire]’s hand on a cutting splice. Even though Tortoise is now known as the poster child of adopting digital editing technology. Prior to that, we were deep into the world of ‘Let’s cut and splice tape.’”

Case in point: at 2:03 of “Cliff Dweller Society,” a new musical piece commences with a drum machine beat supporting a guitar and bass playing a slow, almost narcotized melody. The theme wants to suggest deep calm, but that feeling is undercut by the cymbal work that conjures the sound of sheet metal being ripped. It’s a pulsing, repeated whine that could be unknown communication for deep space. Soon, the deep calm motif recedes, and two organs fade in, who are trying to out-creep each other. The 3:16 mark starts a new segment and it’s all percussion. Notably, Tortoise features three different drummers: Bitney, Herndon, and McEntire. Experiencing a live set of Tortoise, the rhythmic-forward nature of the band is even more pronounced than on studio recordings. This short, minute-long snippet could be an example of all three playing drums at once in the studio. However, Brown said that the band shifted lineups over the course of the “Cliff Dweller Society” recordings:

“At different points it would have been only three of the five of us in the room. Some of the little snippets are just me and John [McEntire] and then, and then we would overdub something. There were definitely some portions where it was all five of us playing together. There was very little in terms of overdubs. I think all of the little pieces that you hear in that collage, some of them are heavily manipulated in the mixing. All of it was put together pre-computer. [McEntire] did not have Pro Tools at that point. We might have even manually spliced that together on tape, I might be wrong about that.”

In the liner notes for A Lazarus Taxon, the box set released by Tortoise in 2006 collecting rarities and B-sides, McEntire wrote that the recordings of the band in “Cliff Dweller Society” were “recorded over the course of one evening.” Brown’s memory is a little different:

“I don’t necessarily recall it being one night. I think there’s part of me that wants to say maybe there were two separate days or nights that we did it…I think there’s somewhere between two and three hours of raw material used for all of those little snippets, maybe even more. That was in an early incarnation of Soma, John [McEntire]’s studio in the Tortoise loft. It was in the very earliest incarnation of that because we had always had a soundproof rehearsal space in that loft that we used. But this was right when he had bought some tape machines and a decent mixer. And he and I both were beginning to collect microphones. We worked at another recording studio, so we could borrow microphones, and we knew other people with stuff. It may be the first thing that was recorded in Soma as a discrete studio. I’m not positive of that, but it was among the first, if not the very first thing…A lot of the ways that we had begun starting to write new material was through improvising together, just kind of playing with ideas.”

This method of exploration can be heard at the 4:34 mark as another new beginning launches with a slightly different rhythm materializing out of the percussion break, this time with bongos. A bass and what sounds like a guitar fade in to accompany this beat. They produce a disconcerting buzzing and other aberrant sounds that could be mistaken for malfunctioning robot technology. This ominous motif quickly fades out as if the band senses only bad things can come from reaching the natural conclusion of that piece.

After a slight pause, the centerpiece of “Cliff Dweller Society” begins at the 5:02 timestamp. The introduction is a guitar playing a jazzy rhythmic part and soon a bassline and drum pattern are determined. The exotica tone is already completely different from what was heard in the previous segment of the track, especially as a group of horns and vibes come in, playing a warm, sexy melody.

It’s obvious that an expanded collection of musicians are joining the five core members of Tortoise here. The additional players include Alex Duvel on trumpet, bassist Chris Lopes, Dan Fliegel providing additional percussion, Evan Coleman and John Sandfort on alto and tenor sax respectively, trombonist Jeb Bishop, Jeff Parker on guitar, and Joshua Abrams on bass. Drawn from the band Scurvy, these musicians were all friends and contemporaries of Tortoise from the Chicago music scene. As Brown put it in his interview: “These were all people in the community.” Some of these names are recognizable, especially Parker, who, along with a few members of Tortoise, would form the band Isotope 217 shortly after this recording. Eventually , he would go on to join Tortoise after the recording of Millions Now Living Will Never Die, thought “Cliff Dweller Society” is his first appearance on a Tortoise recording. Another familiar name is Abrams of Natural Information Society fame, who became an integral part of the Chicago scene after helping to start The Roots while growing up in Philadelphia. Some of the other players in Scurvy have retired from music while others are still active, whether in Chicago or in other locations.

The song played by Tortoise and Scurvy in this main section of “Cliff Dweller Society” is called “Tell Me Once More” and it was composed by Dan Fliegel. How did “Tell Me Once More” become part of a Tortoise track? Brown has the answer:

“There had been an improvising trio on a Wednesday night at a coffee shop that had been Dan Fliegel, Jeff Parker, and Dan Bitney, and the three of them had played [the song] together. We were all familiar with that music. We had heard the song, and I think it was Dan or Johnny [Herndon] who said, ‘We need to play Fliegel’s tune as a portion. Let’s have that be the centerpiece of side B, and then we’ll collage around it.’ We were all like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it. We love that tune.’”

As Brown recollected, the circumstances recording “Tell Me Once More” were hectic:

“That was a whirlwind, because Alex was a taxi driver. I think he might have been on the clock! I think he parked his cab outside of the Tortoise loft and came up…I think we rehearsed it one time, and then we hit record. We did two takes of it, and then half of the people had shit that they had to do and left. I remember [McEntire] scrambling to get the mic set up. It was not multi-track. It was all recorded live, straight to tape. We had a tiny window. I think that the amount of time spent playing that music was less than 30 minutes, including the recorded takes. My recollection is that there were two takes. I might be wrong about that. There may have been one. We may have just played through it twice, rehearsal, and then, boom, record it. Listen to it back. ‘Was that good? All right, see you, get back to work, guys.’ It was crazy, just trying to coordinate all those people’s schedules to be there.”

At 6:16, after completing the main melody, Jeb Bishop takes a solo on trombone. Parker’s guitar rings out throughout as if to affirm the sensual solo and the entire proceeding. The horns provide accents towards the end of the solo also offering their support. The collective goes back to the main melody once again before moving into a bass-centric passage. As Brown emphasized in his interview, there are four basses during this stretch of music: Abrams and Lopes on upright bass with McCombs and Brown both playing electric bass. The group must have recognized the unique situation of having that many basses on one recording, so it’s endearing to hear all four basses push and pull against each other here. Soon, different players take turns in quick little spotlights — the trumpet, vibes, trombone, and Parker’s unmistakable guitar — before all of the melodic instruments begin soloing at once with insistent playing from the rhythm section. The collective build and build to a discordant peak before settling and easing back to the main, sonorous melody. Eventually, “Tell Me Once More” comes to a close with a big ending. It’s a thrilling passage, not only for the beautiful group playing throughout, but also reflective of the warm, generous nature of the Chicago music scene.

Though it seems “Cliff Dweller Society” has reached an end with the natural conclusion of “Tell Me Once More,” yet there’s another beginning at the 10:36 mark. Chimes and bells as well as the drone of static that could be further alien communication provide a background for an insistent main drum part. In this piece, Tortoise takes all of the lessons from Jon Hassell’s Fourth World concepts and initiates their own world-building practice. Seeing the potential of this segment, months after the recording of “Cliff Dweller Society,” Tortoise released a 7” called “Why We Fight” on Soul Static Sound based on this piece:

Everything from the original part on “Cliff Dweller Society” is expanded on “Why We Fight.” Within the context of more drums and diverse tones, an inviting central melody grows out of the surging Hassell Fourth World groove. Soon, a counter-melody is offered while underneath it all is a display of distorted weirdness that sounds like someone is wrestling with a wild animal.

Asked about “Why We Fight,” Brown says “The version that is on ‘Cliff Dweller Society’ is John [McEntire]’s mix of that song. The version that shows up as ‘Why We Fight’ is my mix.” How did “Why We Fight” come to be? Brown’s memories are a little hazy:

“What I will say is possible is that I may have not been a member of the group at that time. And there are a number of ways that that could have come about, which is that at the point that I quit Tortoise, they were extremely busy. They were about to embark on the European tour. John [McEntire] was quite busy as a recording engineer. There was a lot of stuff going on, and there were a lot of requests for songs outside of Thrill Jockey…This is conjecture, but I think that there’s a kernel of truth to this, but maybe I had already quit, but they needed ‘Why We Fight’ to be done on a timeline and then they asked me to do it. I may have been out of the group. I may not have been. I may have been on the cusp of being out of the group, but it was definitely towards the end of my tenure.”

The following year after Brown’s departure, Tortoise released another version of this piece, a new remix by McEntire, named “Source of Uncertainty” found on a 1996 ‘Mo Wax compilation:

On this new version, McEntire strips away Brown’s additions and brings the music back to how it sounds on “Cliff Dweller Society” by emphasizing the chimes and bells. He then adds a few new elements to make it more suitable for dancing at the club, a Fourth World club, of course. The transformation from the raw material that was recorded in Tortoise’s loft to how the piece appears on “Cliff Dweller Society” to “Why We Fight” to “Source of Uncertainty” demonstrates the demand for experimentation that the members of Tortoise place on themselves. They constantly ask, “Can we do something more with this?” This constant building up, cutting back, and creating something new is a hallmark of Tortoise’s entire body of work that continues to this day.

Speaking of experimentation, “Cliff Dweller Society” isn’t over yet! At 12:20, the band ushers in another short beginning, a 15-second morsel of pulsing mosquito-y buzz — perhaps as a nod to the band’s original name of Mosquito before they settled on Tortoise? — that acts as a transition to yet another short groove, complete with eerie, Ghost of Christmas Future effects. This segment fades out and the 13:11 mark sees another beginning fade in. It’s a slice of bass-forward funk that could be confused with one of the instrumentals that Beastie Boys featured on both Check Your Head and Ill Communication. This isn’t unexpected as Tortoise and Beastie Boys were swimming in the same waters in the mid-’90s with different destinations in mind. At 14:06, a slinky groove emerges driven by a chicken scratch guitar and another Fourth World rhythm. Not even a minute later sees the return of the Beastie Boys-esque instrumental from a few segments before. A snippet of that jam is put on repeat, thus concluding “Cliff Dweller Society.” The stretch of small musical slices from the conclusion to “Tell Me Once More” to the end of the track is remarkable. It’s as if someone is in the warehouse shown at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, opening various boxes stored there, and a new exciting Tortoise groove blasts out of each one.

“Cliff Dweller Society” is a singular achievement for the band. Brown is proud of it and states that “Gamera” and “Cliff Dweller Society” represent “the fully realized version of Tortoise that I was in.” He continues:

“I love the first LP, but we were still experimenting. We were doing it on borrowed studio time…We didn’t go into the studio with fully realized ideas; we just recorded the batch of songs that we had. Whereas I think of ‘Gamera’ and ‘Cliff Dweller’ — that is the most exact expression of Tortoise with me in the band.”

The collage-like nature of “Cliff Dweller Society” not only acts as a significant achievement of Tortoise’s development as a band, but also as a link in a chain. The group took inspiration from DAF for “Cliff Dweller Society” and it’s easy to connect the track along with the remixes on Tortoise’s Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters to DJ Shadow’s work on Endtroducing….., The Avalanches’ Since I Left You, and the greater mash-up explosion that followed. Furthermore, the “Tell Me Once More” section serves as a window into Tortoise’s Chicago circle, showcasing the work of peers and friends while also moving the band’s music forward in its ongoing quest for experimentation. Advancement is a renewable resource inside “Cliff Dweller Society” as the musical equivalent of If on a winter’s night a traveler begins again and again and beckons the listener to play the song on repeat so that the beginnings can repeat all over again.

———————–

Many thanks to Ken Brown for his insights, memories, and contribution, both with the interview as well as fact-checking information.